Freight Class Explained: FAK FAQs

02/27/2019 — Jen Deming

There seems to be an endless number of factors that can affect freight class, and in our last two blog posts, we covered the most significant, including product category, materials, packaging, and density. When we talk freight class with our customers, many shippers ask about a potential or existing FAK (Freight All Kinds) rating, and whether it's getting them the best pricing possible. yes, we're throwing another shipping acronym in the mix. We'll take a look at what it is, which shippers quality, and whether or not it really is right for your business.

What is an FAK?

An FAK is a class agreement that is established between a carrier and a shipper, allowing the shipper to move multiple products of different classes at one standardized freight class. Essentially, an average class of all the commodities being shipped is determined, and the shipment gets rated at the same class regardless of the product type, making the price fair for both the carrier and the shipper.

How does this differ from a class exception?

A class exception agreement utilizes an umbrella system that may rate a range of actual class items at a lower class. For example, a business that may ship items classed at 70-200 may be rated at a class 150. Anything above class 200 would ship actual class. A true FAK is extremely rare for a shipper to negotiate with a carrier, as it requires extremely high volume for carriers to determine it worth their while.

How does a carrier determine whether an FAK is possible?

As mentioned above, freight carriers really have a lot of the control and are calling the shots in many parts of the freight industry. A shipper must really be moving a high volume of loads in relatively even amounts in order for lower-classed items to offset higher-classed items, making the compromise worthwhile to the carrier. Originally, when FAK classification agreements were first implemented, they were beneficial to both parties. However, many shippers learned how to manipulate the agreement, shipping risky freight loads at a lower cost, and putting carriers in the hot seat. To combat the misuse of the system, carriers have held back in entering these agreements more now than they used to.

If you are a rockstar at optimizing the packaging and maneuverability of your high-class freight, taking into consideration density, fragility, and stowability, you have a better shot at obtaining an FAK. Basically, if you can get your freight to operate like a lower class, you may be rewarded with a lower class.

What's the catch?

If anything proves true in freight shipping, it's that nothing is as simple as it seems. An FAK can seem like an awesome idea with a few drawbacks, but even if a shipper does manage to acquire an FAK with a carrier, it doesn't mean it's exclusively beneficial. Keep in mind that carriers are in charge and the parameters in place are pretty much at their discretion. If you are not shipping lots of mixed pallet freight, it just doesn't make sense. Small to medium-sized businesses that have one or two major commodity types won't see the same benefits of an FAK as facilities that are mass producing many types of products would.

If you are typically shipping lower-classed items, keep in mind that your "average" class could potentially be higher than your actual class, because you are essentially increasing your minimum charge. It may save you on the one-off shipment, but it's hurting you in the long run. The same goes for a class exception strategy. Carriers are not likely to be open to lumping any of your shipments of a higher class into this tier, no matter how infrequent they are. Because of this, your tired structure will likely reflect a higher average class, which is essentially over-classing your shipments.

Another notable consequence of FAK implementation is that carriers will often limit liability on these shipments. In many carrier tariffs, verbiage is in place that the carrier is responsible for the price per pound on the freight class being paid. This is very different from actual class. If you are shipping a high value load at a very low class, even if the damage claim is won, the payout would be minimal compared to the value of the shipment.

What's my class?

Now that we've gone over how an FAK can affect freight class, let's take a look at an example shipment that would create a difference for shippers with and without an FAK. We can use a hypothetical where we are a shipper with an FAK agreement in place. If the actual freight class of our shipment falls within 70-200, we are rated at 150.

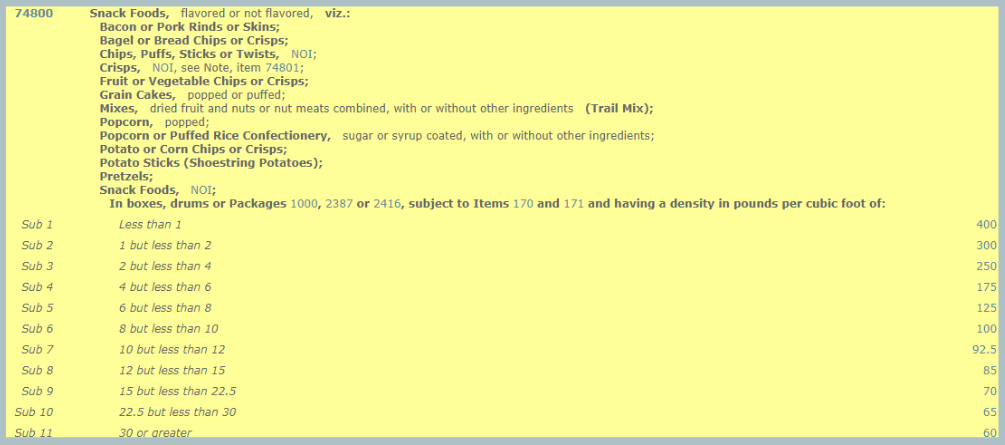

In this example we will be looking at a pallet of popped popcorn, in boxes, measuring 40 x 48 x 52 and weighing 315 lbs. This is a common shipment that would typically be rated as density-based, and would have a high class due to the fact its density is low. We will use ClassIT in order to determine the actual class and compare it versus the FAK.

With the search tool, we use the keyword "popped popcorn." It's important to note the distinction between popped popcorn and popcorn kernels because popped popcorn is much less dense, and a higher-classed shipment than raw kernels. Our shipment best falls into the Foodstuffs Group, which is a general group of foods, beverages, and other types of non-perishable items that are broken down into many articles usually determined by density: